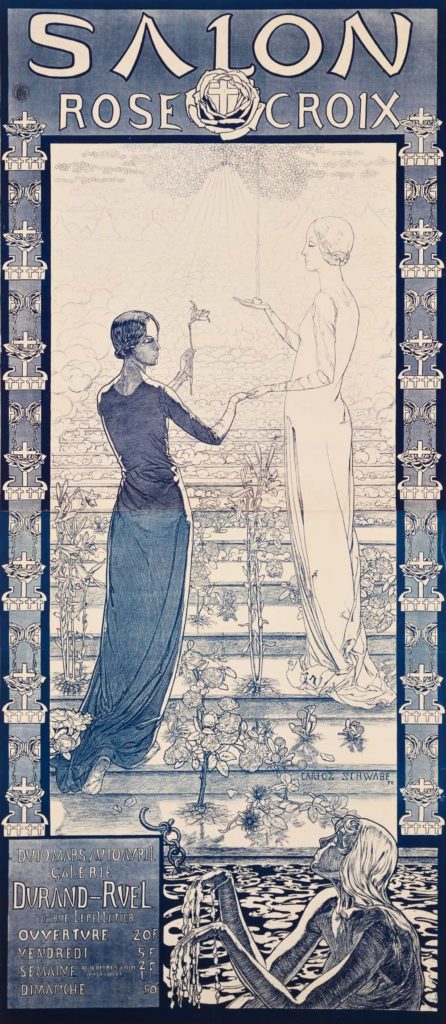

Affiche pour le Salon Rose+Croix

Poster for the Rose+Croix Salon

Lithograph printed in blue on two sheets of wove paper, 1892

Size

195 x 81 cm

Provenance

Private collection, France

Literature

Jean-Jacques Lévêque, Les Années de la Belle époque 1890-1914, Paris, ACR, 1991, pp. 18-19

Exhibition

In the top-three of the most famous 19th century French posters, the present one by Carlos Schwabe, for the first Rose+Croix Salon in 1892, has definitely its place, along with the Mucha for Sarah Bernhardt, and the Toulouse Lautrec for Moulin Rouge. Amazingly, it was the Anglo-Saxons, and not the French, who drew attention to the Rose+Croix Salons, by the essay of the American Robert Pincus-Witten in 1968 and the exhibition in London’s Picadilly Gallery that same year. The cover of the catalogue for the latter displayed the present Schwabe poster. More recently, the initiative once again came from the USA via a double exhibition on the Rose+Croix Salons at the Guggenheim Museum in New York and Venice, with the beautiful Schwabe poster displayed at the entrance. Also, the remarkable exhibition “La Porte des rêves, un regard symboliste” held at the Caillebotte House in May-June 2018 opened with the Rose+Croix Salons and showed the poster for the first salon by Schwabe.

Conceived and organized by Joséphin Péladan, the six Rose+Croix Salons have for a long time suffered from the nefarious – one could say baroque – image of the “Sâr Péladan”, a kind of 19th c. Dali: inspired, genius, but also talkative, scattered and prolific. Going beyond the well-worn clichés, various books, academic works and exhibitions are starting to restore Péladan to his true status as a fantastic discoverer of the talents of the modern avant-garde art. Even though great artists, Moreau, de Chavannes, Redon, who were disturbed by Péladan’s tumultuous activity refused to expose their work, the list of exhibitors is impressive. Of the 160 exhibitors, one third of them are among the international big names of art today. Numerous Belgians, e.g. Khnopff, Delville, Fabry and Montald; of course, Frenchmen: Armand-Jean, Emile Bernard, Bourdelle, Chabas, Filiger, Grasset, Osbert, Armand Point, Rouault, etc. and among foreigners: Holder, Schwabe, Toorop and others. The first salon in 1892 was a considerable success at a time when avant-garde and symbolism figures were subject to mockery. There is nothing of the sort here. It is as if the magic of Péladan, the sounds of Erik Satie, the priestly scenery had transformed an open scandal into a mystical communion.

Schwabe was selected by Péladan in August 1891 to do the poster, and he also exhibited sixteen works, including L’Evangile de l’Enfance. For Jean-Jacques Lévêque, “the narrow, high format of the poster contributes to the ascending character of the work; the blue colour, itself symbolic, suggests a dream, and represents a kind of instruction manual for idealist art.” Schwabe illustrates the evolution of Man (with feminine figures) from matter to spirit, through a design with multiple grid readings. It is clearly an esoteric composition where “the Japanese-style graphics of the inscriptions add to the strangeness of the work.” Schwabe’s design of three female figures in the bottom-up upstairs suggests a hierarchy. In the lower level, the physical Humanity emerges from muddy water. On the staircase, a second figure is advancing. Although dark as in a counter-light effect, this woman appears less material than the first: it is Purity that holds a lily and whose ankle had just escaped from a chain. She gives the hand to a third woman, totally disembodied, who holds a heart, with a thin ascending flame, symbol of Faith. At the top, the mystical ideal, unattainable, radiates like a celestial light. As soon as it appeared, this poster gave rise to all possible interpretations. His message, in the context of the Rose + cross is a call to spiritual ascension through idealistic art. The manifest character of the poster was soon underlined.

Reference

Ruth Malhotra, Marjan Rinkleff & al., Das Frühe Plakat in Europa und Den USA: Ein Bestandskatalog, Berlin, Mann Verlag, 1973. vol. 2, no. 768 (printed by Draeger-Lesieur, Paris)