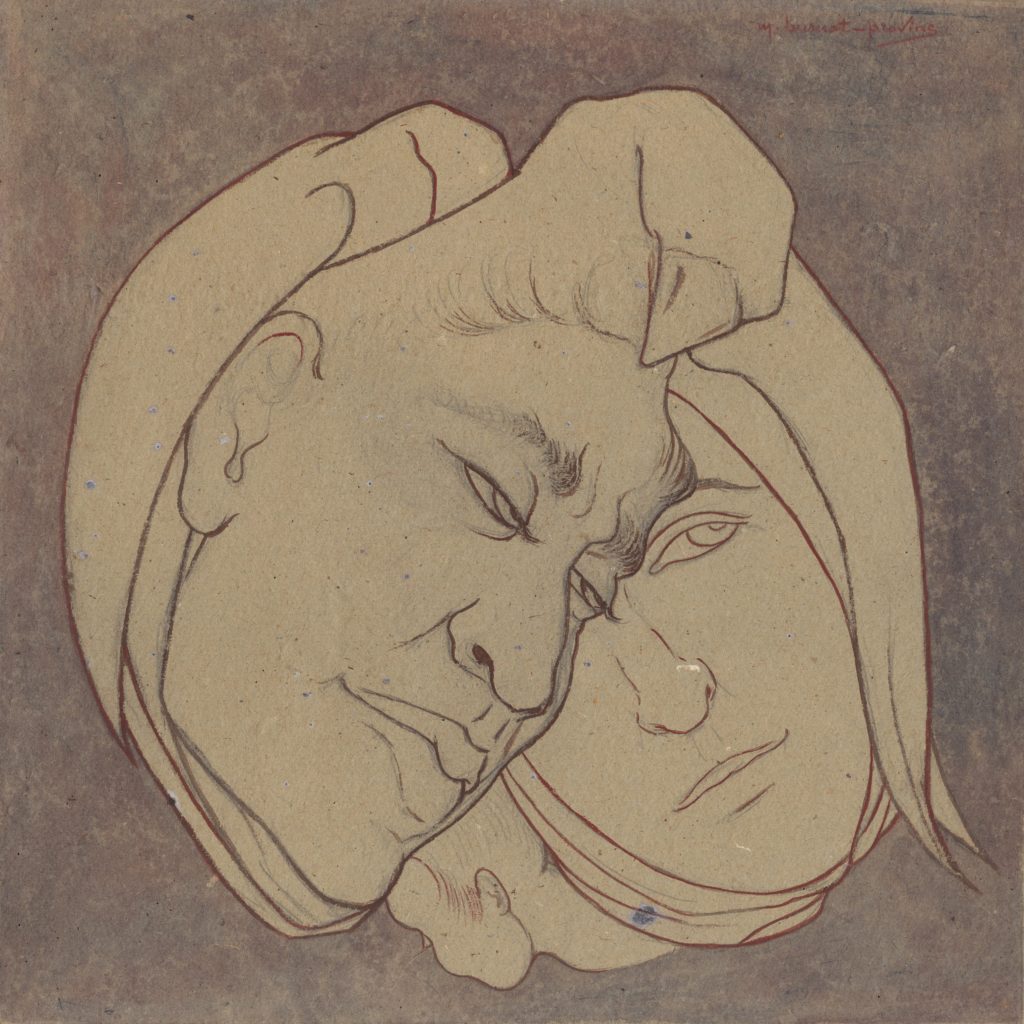

These two spectacular surrealist drawings, La Mort couvée and Mikli affectueux, belong to the most famous series by the French-Swiss artist Marguerite Burnat-Provins, called Ma Ville. « […] It was then that I felt hordes invade my soul; names, names, names by the hundred, squeezed together like people from who knows where. Overwhelmed by this flood, I wrote, in columns and the regiments advanced. And then I painted, a world was born that bears the names I heard. What this world is, I don’t know” . With these words, Marguerite Burnat-Provins described the event that changed her life as much as her career, on the evening of August 2, 1914, when the tocsin of mobilization resounded where she was living, in Saint-Savin in the Pyrenees. October 14, 1914, marked the first physical appearance of a figure distinctly pronouncing her name, and these visions were to come for years and years, they triggered in her an artistic impulse that would constitute Ma Ville, a large multifarious group of drawings as singular as it was original.

Trained at the Académie Julian with the painter Jean-Joseph Benjamin Constant in 1891, Marguerite continued her training at the Académie Colarossi before perfecting her painting skills at the Ecole des Beaux Art of Paris when its teaching was opened to women in 1896. As a rebellious, modern and resolutely avant-garde artist and equally writer, her temperament and her multiple talents were marked by a succession of tragedies: the loss of several members of her family in her youth having caused her both physical and psychological disorders, she was also tormented from childhood by premonitory dreams of violent deaths. Married to the Swiss Adolphe Burnat in 1895, she then moved to Vevey, working with the group of artists led by Ernest Bieler in Savièse until 1905. Then, divorced and also traumatised by the death of her father, she spent her life travelling with her new husband, Paul de Kalbermatten, in Egypt, and living between Bayonne and Vevey (Switzerland) until 1913. But when the World War I broke out, her past troubles resurfaced to mingle with those of the present. The war separated the couple and she gradually settled in Neuilly; she remained until the end of her life in France, especially in the South. She was then very prolific, both by her works and her writings. She was especially appreciated in Paris, mainly because of the direct conjunction between her mental illness and her artistic production, which fascinated many French intellectuals. She was then in contact with the philosopher Edouard Monod-Herzen who was passionate about parapsychic phenomena, with Dr. Gustave Geley, one of the first scholars to have studied her hallucinatory creation; with Fernand Vanderem, an influential literary critic at Le Figaro, with the collector Felix Fénéon, with the writers Henry Bataille, Pierre Louÿs, Anatole France, with the artist Jean-Paul Laurens, the journalist Louis Barthou, the actress Marguerite Moreno, etc.

With her visions that drove her to create, another world opened up to her and she was aware that she was the princess of a royalty composed of ethereal, ghostly and mysterious beings. A dreamlike universe that echoes the tumult of the War that took away several of the artist’s loved ones and that she expressed by a poetry of the strange and the disturbing in aesthetic beauty. This fantastically real and timeless tale is a direct emanation of Marguerite’s troubles and psyche, like a part of her soul put down on paper.

The particularity of Marguerite’s work to which she devoted the rest of her life, as a medium was associated with her solitary side, living recluse, marginalized by the world she created for herself, and the use of poor recovered materials due to the lack of financial means resulting of her will of independence. This pushed Jean Dubuffet, then setting the concept of Art brut, to be interested in Ma Ville, after having heard about it by Doctor Gaston Ferdière in 1945. However, as the Burnat-Provins’ training and career ran counter the definition of Art Brut in that it brought together artists who had no artistic or cultural training, and who created mainly by instinct, Dubuffet changed his mind and did not include Marguerite’s work in his collection. The Musée de l’Art Brut in Lausanne was based on Dubuffet’s collection and theory, but notwithstanding in 1979, it was decided to place the Burnat-Provins series in a section entitled Neuve Invention, as if to better underline the originality of this elusive and unclasifiable artist. Indeed, Marguerite Burnat-Provins knew how to mix the different artistic currents that marked her career, such as the Symbolism that was undeniably inherent to the spirit of her work, her total freedom of expression, as she herself described it: « I loved art and life passionately, I listened to what was singing within me, I followed my path » .

La Mort couvée reflects not only Marguerite’s fascination with the animal, but also her academic training in the use of the symbolic skull as a vanity. The two birds brooding over the skull in their Japanese touch, in vogue at the end of the 19th century, can evoke both the artist’s terrifying pre-war premonitions and her inability to give birth, a personal tragedy she learned of at the age of only seventeen. This work therefore resonates with the distress and suffering of a woman who was never able to experience the joys of motherhood and who devoted her entire life to defining her own style and generating her art.

Among the beings of this substitute family created by the emotional void, the birds dear to the artist hold an important place and their recurrence has given rise to a sub-series called Série des figurines avec des oiseaux, to which belong these two sheets we offer. Mikli affectueux is a typical example of hybrid figures that are both anthropomorphic and zoomorphic, precisely mixing the human and the bird. It also shows the complexity of the artist’s work in its codification, since Marguerite through her visions, transcribed not only the physical aspect but also the personality and temperament of the figures, in the systematic association of texts with the images. The use of graphite and watercolour specific to this work, allowed her to play on the variations in intensity and to enhance the unreal aspect of this universe.